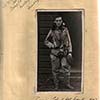

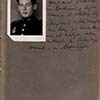

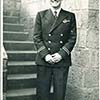

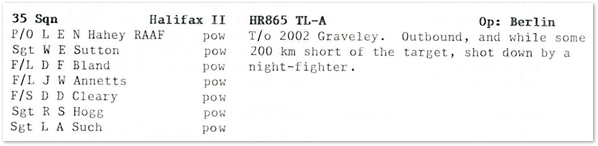

Daniel David Cleary

- Born Liverpool 13th February 1922

- Enlisted 30th September 1940

- Temporary award Path Finder Force Badge 28th June 1943

- Shot down 23rd August 1943

- Captured outside Gentin,

south of Magdeburg 24th August 1943 - Detention Dulag Luft – Oberursel

24th August 1943 – 28th August 1943 - Arrival at Stalag IVB, Muhlberg on Elbe

1st September 1943 - Permanent award Path Finder

Force Badge 25th August 1943 - Promotion to Warrant Officer

24th July 1944 - Camp “liberated” by Russians

23rd April 1945 - Released from Camp 4th May 1945

- Marriage 7th June 1945

- Death 23rd February 1979

Operations Record Book, Graveley. The National Archives Air28/322

Night 23rd / 24th August 1943 Time 20.07 to 04.00

Attack on Berlin

“In accordance with orders contained in Form B.357, 23 Halifax aircraft of 35 Squadron took off from Graveley to attack Berlin in cooperation with 100 Path Finder Force aircraft and 616 Halifax and Lancaster bombers of other groups. Weather in the Berlin area was clear with slight haze. Blind markers opened the attack on time and a circle of red target indicators was dropped into which Backers Up placed a concentrated cluster of green TI. The attack developed well around the markers and soon many fires were taking hold and a column of black smoke rose to 15,000ft. Several big explosions were reported, one of which was severe. The attack appeared to be on districts in the south west and west of the city. Flak was only of moderate intensity but large numbers of searchlights were in operation and were cooperating with many night fighters which immediately attacked any aircraft coned. 15 Halifax aircraft of 35 Squadron successfully attacked the Primary; 4 returned early for technical reasons and the following aircraft did not return; A/35 Captain Pilot Officer Lahey, G/35 Captain Flight Sergeant Arter, H/35 Captain Flight Sergeant Williams and R/35 Captain Flight Lieutenant Webster (Group Captain BV Robinson, Station Commander, was a passenger in R/35).”

Extract from Royal Air Force Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War – 1943 (Vol 4).

By WR Chorley (1996; Midland Publishing) page 280. Unfortunately Chorley mispells our Pilot’s name, it’s Lahey not Hahey.

On the night of 23 August 1943, “A for Apple” Path Finder crew were at the front of 700 bombers on a raid to Berlin.

Wilf Sutton, one of the crew, describes the moment they were shot down:

“We broke cloud east of Hannover and within minutes we were straddled with 20mm cannon shell from a Junkers 88 … as soon as the first shells hit us the skipper went into violent evasive action … when he righted the plane I could see what a mess we were in. Cannon shells had ripped through the fuselage within an inch of my flare chute position, torn the starboard wings apart, set the two starboard engines on fire and the 1000 gallons of petrol. None of the 7 crew members were touched.”

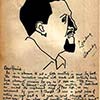

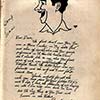

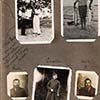

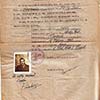

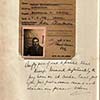

The War Log on this website belonged to the Wireless Operator on board, Daniel David (he preferred David), and tells of the next 20 months as a prisoner of war and beyond. I’ve always called this his War Diary but it’s not a narrative. Instead it is a collection of photos, sketches, news cuttings, letters, poetry, mementos and ephemera.

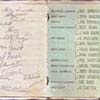

David enlisted on 30 Sept 1940 when he was 18. He trained as a Wireless Operator/Air Gunner. Len Such enlisted on 27 June 1940 and was recommended to train as an Air Gunner. Len introduced David to his sister Beatrice and they married after the War. Of the other members of the crew: Lahey, Hogg, Annetts and Bland, I have very little information. They were all officers so were sent to Stalag Luft III.

I was fortunate to meet Wilf Sutton in November 2003. He told me that the crew became a crew in Marston Moor, Yorkshire. In January 1943 they went along to a talk about the new Path Finder Force whereupon their pilot, Laurie Lahey, applied for them to be transferred. The selection process was tough but they were considered an experienced crew because of their 8 ops with 77 Squadron.

After they were shot down, David spent 4 days at a Dulag Luft (interrogation and transit camp) at Oberursel near Frankfurt. He was then transferred to the Wehrmacht-run camp Stalag IVB, Muhlberg on Elbe. Infamous for being one of the largest in Germany, it held 16,000 men but this swelled to nearer 30,000 by the end of the war.

The War and his detention had a massive effect on David’s life. At such a young age, it must have been an exhilarating adventure leaving school and heading straight into the RAF. Life in the camp was obviously hard but that doesn’t really come through in the Log. Instead, we see a young man in his element: writing poetry, telling stories and coming to terms with his situation. After being demobbed, he married Beatrice and initially worked in the telephone exchange at Faraday House. However, by 1946 he had taken a job with BOAC as a flight steward and spent the next 15 years flying.

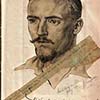

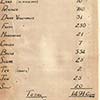

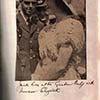

Some pages of note in the Log are: page 49 – Hitler photo taken from dead German & story; page 51 – Letter from actor Robert Morley; page 60-62 – forged documents for an escape attempt; and my personal favourite page 127.

David’s collecting also extended to cast lists and programmes from Camp theatre productions (starts page 39). This is a good opportunity to mention David’s finest moment in the Camp, his portrayal of Sheridan Whiteside in “The Man Who Came to Dinner”. By all accounts it received rave reviews. Wilf Sutton discusses the camp theatre in the following newsletter; www.prisonerofwar.org.uk/winter_2005.htm. Some of the info he gives differs slightly from what I have gathered from the Log but this doesn’t detract from either.

Returning to the Log, there are also the more unusual inclusions such as a camp “blanket” chit on page 59 and a camp “beard” chit, authorising him to wear a beard for “theatrical purposes” on page 52. I’m not sure how he managed to hold onto a bit of burnt parachute and a piece of “window” but these can be found on page 118. After the war he included the RAF correspondence telling of his detention and he continued to collect Pathfinder news cuttings. The last news cutting is from 1976, fittingly it tells of the demise of the Pathfinder Club on Mount Street.

I have transcribed the Log so that it is easier to read, my comments are in square brackets. The Log is not in chronological order because, I believe, David received the log fairly late into his detention (possibly Oct 1944, if we go by the page entitled “front inside cover”). He must have realised that in order for the log to appear sequential he had to leave some pages blank, mostly at the beginning for photos etc. He doesn’t quite achieve this as you will see when reading through.

Apart from the letters, which I have placed at the front of the Log by date, I have not changed the order significantly to allow this disorganised feel to come through.

————

6 May 2010:

The Curator of the Pathfinder Museum, RAF Wyton replied to a letter I sent with the following piece of information: “It would appear also that Daniel’s Halifax may have been shot down by Major Streib in a Heinkel 219s, an advanced variant of which only 2 were in operation at that time. HR865 was also the first PFF aircraft shot down that night.”

————

2 Feb 2012:

There is a good description of the raid on Berlin on the night of 23rd August by Michael Cumming in his book Pathfinder Cranswick (London, William Kimber 1962) p117. Cumming is describing the last raid that Group Captain BV Robinson made (all dead, HR928 TL-R).

“The target that night was Berlin – the seventy-fourth RAF assault on the German capital and the heaviest up to that time. Group Captain Robinson briefed the Graveley crews himself and a groan went up when the target was announced for no-one relished the prospects[sic]. The Germans knew that an attack on Berlin must come soon for the nights had drawn long enough for the RAF bombers to get to Berlin and back under the cover of darkness. The Jerry defences were ready – and the bomber crews at the RAF bases knew that, too. When the bombers were nearing Berlin the sky became alarmingly clear. It was then that the trap was set. Enemy night-fighters soared away from their airfields to wait in ambush high over the expectant city. As the Pathfinders reached Berlin the fighters pounced. One bomber pilot saw fourteen fighters in the space of three minutes. The raid was one of the most concentrated up to that stage of the war with more than 1,700 tons of high explosives and incendiaries tumbling down within fifty minutes – double the weight of the previous heaviest assault. Yet the success of the raid was marred by the toll taken by the enemy defences, for fifty-eight bombers failed to return. It was Bomber Command’s most costly raid up to that time.”